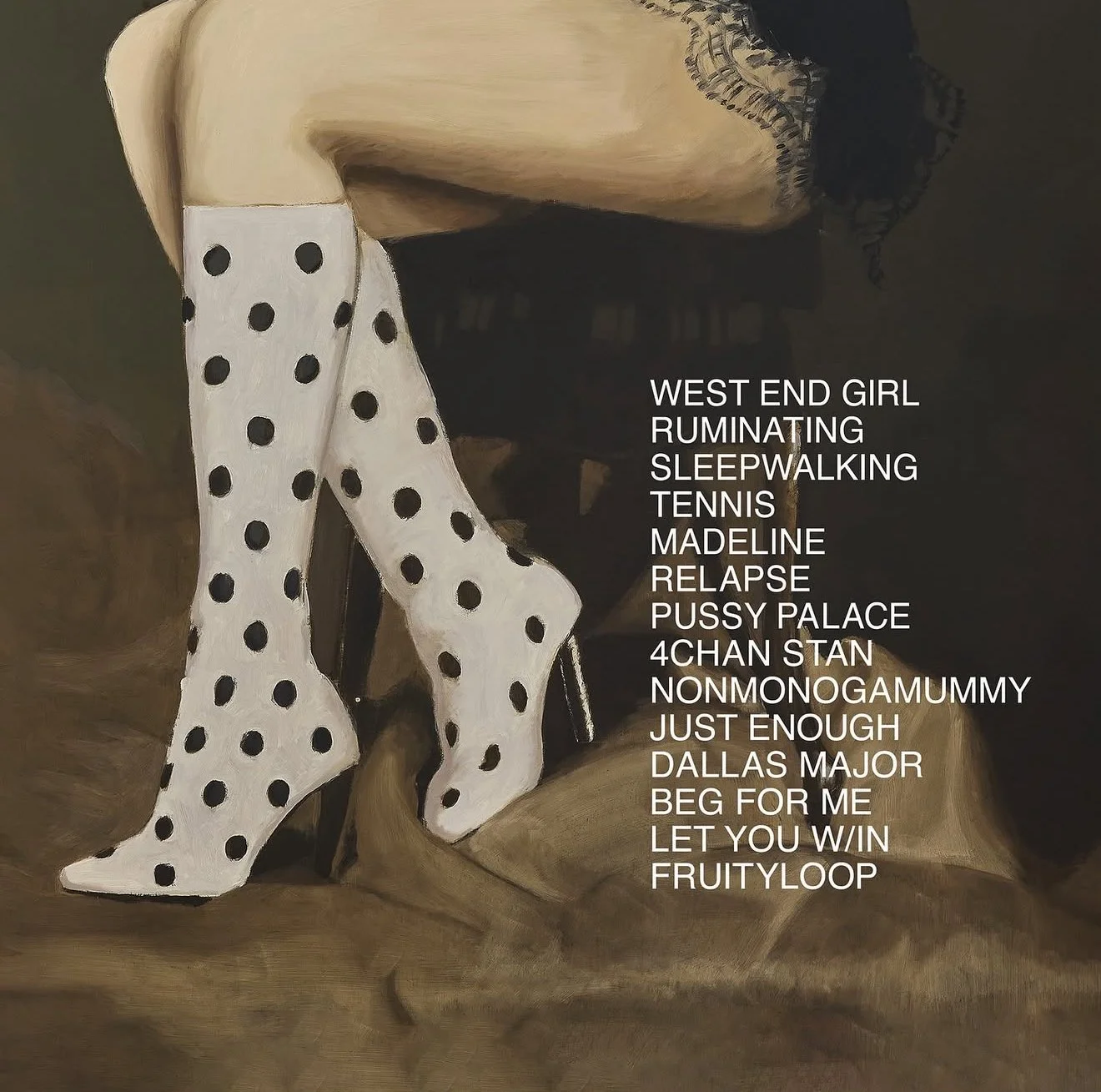

The Gothic World of West End Girl

Mairéad Wiley

Across fourteen tracks recorded in just sixteen days, Lily Allen’s West End Girl offers a scathing portrait of an unravelling marriage, charting an unwanted open relationship, affairs, and her divorce from actor David Harbour. The album’s fixation on homes and houses carries a distinctly Gothic charge, unfolding like a modern haunted-house story in which the domestic space becomes uncanny – its architecture mirroring the relationship through thresholds, secrets, and shifting boundaries. Physical spaces reflect emotional collapse throughout as Allen loses herself in the roles she’s expected to play. She becomes trapped within the very domestic world that once promised safety.

The opening track, ‘West End Girl’, begins with the promise of stability. Over a light jazz arrangement, Allen recounts moving to New York, buying a brownstone, sorting the mortgage, and furnishing a shared life. As she turns the key in the door, she gets a call offering her the lead in a London play. The doorway – a Gothic threshold – becomes a point of rupture. Once in London, the song disintegrates into a phone call in which she reluctantly agrees to an open relationship. The structure that seemed so solid buckles and rearranges, leaving Allen trapped inside. In true Gothic fashion, she begins to unravel within these confines.

With its repeated lyrics and looping autotune, ‘Ruminating’ depicts Allen haunted by images of her husband with other women, while the lullaby-like melody in ‘Sleepwalking’ sustains this psychological haunting. She drifts ghost-like through the marriage, gaslit into questioning her perception. Her husband’s refusal to leave, to touch, or to love her properly confines her within the corridors of both the house and the relationship, eroding her sanity like classic Gothic heroines in narratives such as The Yellow Wallpaper.

‘Tennis’ marks another disruption of domestic order. Allen attempts to perform the role of dutiful wife and mother, glad to have her husband home. That is, until she reads his messages and discovers he has been playing tennis with another woman – an intimacy he denies her. In ‘Madeline’, this boundary collapse deepens: ‘It had to be strangers, but you’re not a stranger, Madeline’. Allen fears the affair has entered their home: ‘I’m not convinced he didn’t fuck you in our house’. The song ends with Allen mimicking Madeline’s voice; she becomes a Gothic double, infiltrating the most intimate corners of Allen’s life, blurring boundaries between self and rival.

‘Relapse’ equates physical dislocation with emotional collapse: ‘The ground is gone beneath me […] I’ve moved across an ocean from my family, from my friends’. Her identity unmoors alongside the destruction of her marriage, recalling the displacement of women in texts like Wide Sargasso Sea. She is isolated, dependent, and precariously balanced on the edges of sanity and sobriety: ‘Can you bring me back while I’m climbing up the walls?’ This fracture continues in “Nonmonogamummy” where Allen recognises her isolation in a space that was supposed to serve her: ‘We built a palace on the perfect street, you really sold me on a dream’. Attempting to be open and a ‘modern wife’ she feels herself slipping, confessing, ‘I’m so committed that I’d lose myself ’cause I don’t wanna lose you’. In ‘Dallas Major’, Allen loses herself completely, shedding her name and attempting to reshape her identity entirely.

The album reaches its most vividly Gothic domestic moment in ‘Pussy Palace’. After expelling her husband from their home, Allen visits his West Village apartment to return his things. Once again, she pauses on the threshold. With her key in the door, she realises something is wrong. Inside, she finds a room haunted by his ‘double life’: a shoebox of letters from heartbroken women, bed sheets strewn on the floor, another woman’s hair, and a bag full of sex toys. Pitchfork refers to the apartment as ‘Bluebeard’s dungeon’, recasting the husband as both Gothic double and villain, divided between two homes, two identities, two incompatible selves. Doubling continues in ‘4Chan Stan’, where a receipt for a gift to another woman haunts Allen’s mind: ‘Why won’t you tell me what her name is… is it somebody famous?’. Here, the blurring of public and private reaches new heights. Having been showcased in Architectural Digest tours, their homes are not only haunted by other women but by public scrutiny.

Yet unlike many Gothic heroines, Allen escapes. In ‘Let You W/In’, she acknowledges her invisibility: even after the divorce she remains tasked with protecting her ex-husband’s reputation, lying to her children and those around her. Ultimately, she chooses to rebel, refusing to be a victim: ‘Already let you in, all I can do is sing, so why should I let you win?’. She concludes, ‘But I can walk out with my dignity, if I lay my truth on the table’. This is what she does with this album, which she closes with ‘Fruityloop’. In the final song, Allen flips the roles, it is her husband who is trapped, doomed to repeat the cycle.

West End Girl is more than a breakup album. Its use of digital fragments like texts, calls and emails aligns with the epistolary Gothic tradition. In novels like Dracula or The Turn of the Screw, letters and diaries reveal partial truths, heightening suspense and uncertainty. Similarly, West End Girl’s digital evidence is incomplete, unreliable, and therefore haunting. In the Gothic manner of texts like The Haunting of Hill House, the album reveals the enduring dangers of the home for women. The Gothic home may now include open relationships, sex toys and West Village apartments, but its truth remains: the domestic is still dangerous.

Photos via Lily Allen / Instagram